In The Mean Game, John Wall Barger holds up a courageous mirror to nature. We don’t get a Disney-fied version of life. Rather we get the requisite amount of joy and sadness, of humor and violence. Barger has a deft touch with language, using it to produce an array of emotional responses. That’s not to say his poems lack intellectual heft. They don’t. But he leaves it up to the reader to decide how much the poems will be interpreted as intellectual exercises and how much they will be regarded as emotional journeys.

While he seems intent on making the reader go though something in the theater of their mind, he also seems resolved not to want to generate any particular meaning or lesson. For this reason, readers should be aware of sudden shifts in the poetic narrative.

Take the poem “The Problem with Love,” in which a boy inherits his dead brother’s pet tarantula. His mother asks if he is “fucking man enough” to take care of the spider. The boy says he is. Barger teases us with normalcy, almost as if this poem is a meditation on adolescence, on growing up. The boy cares for his new pet, feeds it and tells it stories. But after a bad dream, he

woke in the dark, found Ma’s hair scissors,

reached into the spider’s house

& cut off a leg.

This sharp turn of events continues spiraling out of control, as the boy cuts off all the legs—twice—until they do not grow back. The spider

sat in her house,

gray, hissing like a punctured

basketball.

The reader may still be tempted to interpret this poem as a commentary on growing up, especially when the boy sacrifices the spider to ants, as if giving up his old self. But the reader has to be careful not to get too invested in having the poems be didactic. They may start out as if there is a lesson to be learned, but they then become something else, more thorny and complicated, like life.

In this particular poem, we may have to go back to the title—“The Problem with Love”— for a clue of Barger’s intent. A common theme in this book is how ineffectual love can be, how love on its own doesn’t necessarily solve problems. The boy’s mother spends her time watching TV, leaving him on his own. After the legless spider is devoured by ants, the boy

hosed down the fish tank.

It took ten minutes to scrub it

spotless, so the sun

really shone through the glass.

Is Barger hinting that the problem with love is that it kills, and what it kills can be scrubbed clean and forgotten in the glinting sun? It could be, but this is one of the defining characteristics of Barger’s poetry: We intuit there’s a lesson to be learned but we’re not quite sure what it is. Barger is a wonderful tightrope artist. He toes the line between darkness and light, between illusion and reality.

“The Bureaucrats” is an example of this tightrope act, and it also contains my favorite opening line: “We never should have crossbred the bureaucrats with office supplies.” At first, the crossbred bureaucrats are valued for their interesting feats, “With microchip eyes, they send emails by winking, With opposable big toes they operate four staplers at once.” But they are being held against their will and escape. In the wild, they undergo a transformation and surreptitiously return. Barger writes, “One day at the mall there was a bureaucrat chewing a cheeseburger.” No one knows how or when they came back or how they took control. He then writes, “And just like that, without fanfare, the bureaucrats were in charge.” The poem could be read as a modern-day cautionary tale. But instead of The Office meets The Lion King, we get Big Brother meets Hannibal Lector. As in all bureaucracies, there are forms to fill out and penalties for mistakes. But in Barger’s world, the bureaucrats “wear our scalps as purses. Our spleens, they say, are delicacies. In broad daylight, I come across three bureaucrats crouched over a body in the street, feasting on it like starving boars. Leaving no waste.”

And so ends the poem, balancing whimsy and atrocity. But Barger’s narrators rarely have use for such labels. No, Barger is a skilled linguist and the moralizing, if any, takes place within the mind of the reader.

There’s a wonderful imaginative freedom in reading Barger’s poems. The language, for example, is often archaic or antiquated, adding to the poems’ mystique. In the opening poem, “Urgent Message from the Captain of the Unicorn Hunters,” the narrator says of the unicorns, “Enough have they tholed.” Thole can be found in Beowulf. It is an Anglo-Saxon word meaning to suffer in silence, without complaint. It is the perfect word to use here because the narrator is asking his listeners to “release” the unicorns who have done no wrong,

Those sealed in your attics. Those chained in our barns. Those on the nightmare yokes.

Those heads on your walls. This is our fault.

Most of the language in The Mean Game is simple and straightforward, even if the ideas and images are complex and layered. On occasion, like with “thole”, Barger sends the reader to the dictionary. In the “Last Book of the Last Library on Earth,” the narrator recounts:

A heavy iron volume burst out

a stained glass window

to the stones at our feet

A scholar plunged after.

Our brothers of the light guns

& clear shields

spattlecocked him.

Spattlecock is an old Irish cooking term from the 1700s, which means to remove the backbone, generally of fowl, for easier grilling. The use of the word adds to the ancient feel of the poem, which also contains one of Barger’s many brilliant poetic descriptions: “I staggered away / in the kiln of dusk clutching it”.

Another poignant description is this one: “Her body held his thunder / the way language holds a flower.” This occurs in the poem “A Scornful Image or Monstrus Shape of a Wondrous Strange Fygure…” (the full title is much, much longer).

In “Tale of the Boy and the Horse Head,” one of the darker poems in the collection, Barger wonderfully captures the morning hue with this line: “Below, in the castiron dawn….”

Finally, in “The Fathers of Daisy Gertrude,” Barger’s deft poetic touch is on display when he tells us:

She slept

under a flowering tree

beside her scream

which remained quiet.

These are just a few of the many examples of how Barger can mesmerize us with his language. We are already in full throttle mode reading these works, a feat that the poet accomplishes, in part, by not using stanza breaks. Barger told me that while writing this book he was influenced by the poet James Tate who, in his later work, didn’t use stanza breaks. He says,

One reason for stanza breaks is to give the reader a little pause, a breather, to collect their thoughts. By not giving stanza breaks, Tate doesn’t allow the reader to rest and possibly break the spell. I was trying for a similar effect in these poems, to hold the reader, to grip them close for the time of the poem, so that there would be no break to the tension until the poem was over.

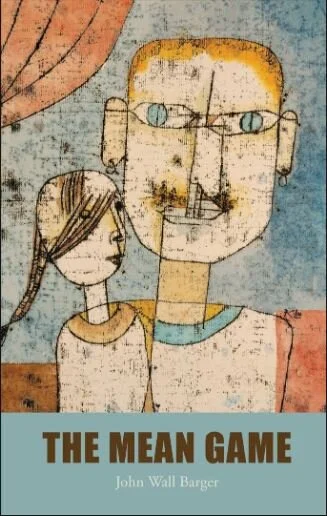

Barger was born in New York City but grew up in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He’s lived in various places around the world including India, Finland, Greece, and Hong Kong, and now resides in West Philadelphia. He teaches at the University of the Arts and La Salle University. The Mean Game is his fourth full-length poetry book, and his artistic maturity shows.

The Mean Game is a book that embraces opposites: joy and sadness, humor and violence, animals and humans, myth and matter. Barger’s poetic muse gravitates towards myth. Myths aren’t afraid to tackle the difficult subjects, to use violence and death as teachers. We are under a certain illusion that our happiness—our marriages, our jobs, our friendships—will last forever. Barger’s poems do not harbor that illusion. They disrupt our normal expectation, and do so with exquisite poetic skills.

I’ll close with these lines from the last poem in the collection “This This is the End.” They portend new things to come, hopefully also from this author:

And when and when the last bird shuts its eyes

And the flesh of the last whale

Drifts like pollen in turquoise ink

And dust devils are lords of the squares

And trees reclaim the stairs

Still the stars glister like sparklers

Aloft in the hand of a girl

Still the earth our grave hurdles with grace in the dark

Chris Kaiser’s poetry was published in Eastern Iowa Review, Better Than Starbucks, and The Scriblerus. It appeared in Action Moves People United, a music and spoken word project partnered with the United Nations, as well as in the DaVinci Art Alliance’s Artist, Reader, Writer exhibit, which pairs visual art with the written word. He’s won awards for journalism and erotic writing, holds an MA in theatre, and lives in suburban Philadelphia.