Fiction for Poets

in which one poet writes to other poets about writing fiction

Plot for Poets

Plot – or more accurately lack of plot – is probably one of the main reasons why I write poetry. Action is not the point. A poet is rarely asked: “So… what happens in your poem?”

Sure, we get: “What is your poem about?” or “What does it mean?” And then we have to wrestle with an appropriately “poetic” sounding response: It’s about the time I narrowly avoided hitting a fox on my way to work. Or …the bond between humans and animals. Or …the existential angst of young motherhood. Or my personal favorite: I could tell you what it means to me, but I’m more interested in hearing what it means to you. In other words: I have absolutely no idea what it’s about.

The point is: when I write a poem, I don’t have to think about things like rising action or falling action, the three act structure, or (god help me!) the arc (at least not consciously… but that’s a conversation for another day). As far as I’m concerned, that’s a very, very good thing – because, of all the overwhelming, slippery aspects of fiction, for me plot is the most overwhelming and slipperiest. In fact, until a year and a half ago, I was pretty sure I couldn’t successfully plot a story about crossing a room.

But when I found myself writing a novel, I realized I was going to have to reckon with my fear of my plot, and I’ve done that by approaching it in the most simplified terms. To be clear: “Simplified terms” does not equal simplified stories. Rather I’ve found three approaches that seem to apply to almost every good story while also demystifying some of the circumspect, lit-speak that can be mysterious and intimidating.

So, here they are…

Three basic ways that I like to think about plot.

Individually and together, the three ideas below have expanded my understanding of plot – not just what plot is or how you do it, but why it’s important. I believe they’re analogous to the various camera perspectives in film – moving from the widest, long shot that takes in the whole thing without a lot of granular detail; to the medium shot that moves in closer, but is still focused on mostly broad strokes; to finally the zoomed in close up that really starts to hone in on details. I find this helpful in terms of thinking about whether a story is working overall and then considering how to refine and strengthen the way it works.

1. Energy transfer.

George Saunders describes plot as a transfer of energy. In A Swim in a Pond in the Rain (recommended in my first post), he writes:

We might think of a story as a system for the transfer of energy. Energy, hopefully, gets made in the early pages and the trick, in later pages, is to use that energy. (p. 35)

and

Energy made in the early pages gets transferred along through the story, passed from section to section, like a bucket of water headed for a fire, and the hope is that not a drop gets lost. (p. 54)

I love the idea of the energy transfer because it is something that we naturally sense – especially poets. As both a and a reader, I can usually feel when something has energy and is moving; I can also feel when it is losing energy (maybe going off course or becoming less interesting). Saunders’ explanation gives us the freedom to trust our writerly instincts without applying some rigid external rubric, model, or structure.

So... as you write, ask yourself: Is there energy here? Is it moving? Am I losing any of it? How do you know if there's energy in a story? Well, it’s not much different than knowing if there’s energy in your poem. Do you feel compelled to keep reading? Do you feel propelled forward? Does each line make you want to read the next?

As poets, we do this all the time – not necessarily in the same way, but we do it. The moment I realized that, I knew I had within me the power to make a plot work in my own way.

2. The Main Moves

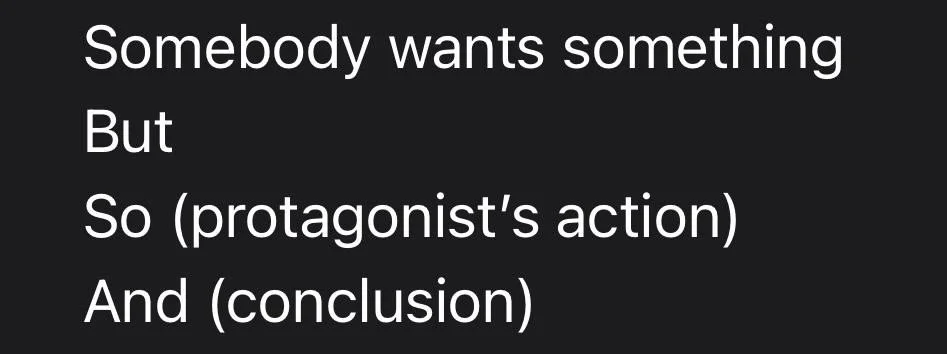

A few years ago, I asked a friend of mine, a fiction writer, to explain plot to me. This was her response:

3. Story Beats: But... Therefore...

Everyone’s seen South Park, right? If you haven't, stop what you’re doing and go watch an episode – any episode will do. It’s an incredible show (however crass or offensive it may be at times), and it’s been around forever, partly because Matt Stone & Trey Parker know how to put together a solid story.

Check out this two-minute video in which they offer some of the most simple and useful advice available for thinking about and moving through a story.

"But... Therefore..." Matt Stone and Trey Parker (South Park) Plotting Advice

I find this helpful for both planning and evaluating. If you’re the kind of person who outlines, you can think about your bullet points as being strung together by but’s and therefore’s. Or, if you’re reading through something you’ve already written, ask yourself if it’s being held together by but’s, therefore’s, or and then’s. If we go back to Saunders’s idea of energy transfer being like “a bucket of water headed for a fire, and the hope is that not a drop gets lost,” we can see that these are the places in our stories where water is tipped from one bucket into the next. Every “and then” is a place where the water spills a little, the momentum is lost; those are opportunities for more causality, consequence, and ultimately tension.

As I said, poets are rarely taken to task about what “happens” in our poems, yet I believe most of us have a greater capacity for plot than we know. So much of poetry is a meditation on how and why things happen around us. As such, poets are keenly attuned to those moments in life where the energy transfers happen. If we take the time to try, I think many of us could plot – not just successfully but beautifully.

Autumn Konopka is a writer and teaching artist who enjoys coffee, running, and reggaeton. She's currently working on her first novel, which she expects to publish in early 2023. Find her online: autumnkonopka.com.