Review of Rocky WIlson’s Dance with Me

December 23, 2020

The first time I saw Rocky Wilson perform, I was sitting at a table in the back of the upstairs bar at Fergie’s Pub in Philadelphia. I was quietly sipping on a beer and waiting for the Moonstone Poetry reading to start. The room was packed with a lot of unfamiliar faces and there was an electric energy in the air. I kind of felt like a stranger who had successfully integrated himself into a party he had not been invited to. Soon the host began his introduction, during which he referred to Rocky as “The Puppet Laureate of Camden.” I was a bit perplexed as I watched this eccentric, older gentleman take the stage and place a monkey puppet upon the podium, to great applause no less. With a smirk on my face, I thought to myself, “Who is this guy”?

After the fanfare quieted down, he cracked a few successful jokes and began to read to us. Well, it was not long into his set that I realized why this poet is so revered. Much like the man himself, Wilson’s poetry draws you in with touches of theatrics, humor, and an undeniable ability to connect with its audience. With a breezy wit and gift for creating genuine emotion, Wilson crafts poems that feel like stories you need to see to the end. Nowhere is this more apparent than his latest chapbook, Dance with Me.

In the book’s biography, Wilson states that his intent was to blend “his love of dance with his love of poetry,” and he succeeds because, like a great dance partner, Dance with Me takes you by the hand as it leads you through 17 poems exploring the many dynamics of human relationships. Every piece in this collection feels as though it is a personal conversation between the author and the reader. The poems are intimate and vulnerable yet offer a sense of optimism. They look into the past not with regret, but with astute reflection. Wilson wants to celebrate the lessons he has learned, and he wants the reader to be there with him as he does. Quite a few poems in Dance with Me focus on Wilson’s immediate family. The first poem “Starless Night” begins in a humorous tone as it describes how his family began, “Mom and dad getting hitched and me hiding way back in their thighs…” He talks about how his sister “…came out like Van Gogh with only one ear.” Yet, by the end of the piece we learn that Wilson’s younger brother did not survive his birth. Throughout other pieces in the book, we see that the loss of his brother has stayed with Wilson to this day. In “Namaste, Angels,” we find the poet musing about who his brother might have been: “Was my little brother ever happy? Well, he never had to wear hand-me-downs or eat Brussel sprouts.” Although it may seem melancholy at first, there is a sweetness to how he writes about his brother. It’s as if he is trying to instill a life in his brother that he was never given a chance to make on his own.

This honest way of honoring the people Wilson loves, living or dead, extends to many other pieces in Dance with Me. In “Blackberries,” we find the author reflecting on how he now takes care of his father after so many years of the opposite: “Feeding him now, he who fed us or at least paid for so many meals.” The next two poems offer a perfect segue into each other and the prior. In “Bloodlines,” you learn that Wilson’s father was drafted into Vietnam and how it affected his grandmother. Wilson writes, “Gram prayed that if it came down to it, his life be taken first. She didn’t want him to live with another man’s life on his conscience.” With the following poem “What Do You Want?,” Wilson describes how when his grandmother died, the only belonging of hers that he wanted were locks of her own hair that she had saved: “I want to look at it again and feel it and smell it and remember Grace.” These poems feel as interconnected to each other as the poet is with his own family’s past, present, and future. They truly are a highlight of Dance with Me.

One of my favorite moments in the book comes with “Dear Mr. Cohen.” Here we find Wilson crafting the poem as if it were a letter to his late idol, Leonard Cohen. In the poem, he asks Cohen to sing his famous song “So long, Marianne…” to his recently deceased friend Marianne: “You can sing that song to her yourself now, Leonard, or better yet, “Hello Marianne…”. Dance with Me is filled with so many beautiful and unique odes like this. It is quite obvious that Wilson’s words show a true appreciation for life, even in death.

Throughout Dance with Me, Wilson’s love for dance and performance are highlighted perfectly in some of the book’s more playful pieces. In “Sunday Matinee,” we find the poet at a performance of Romeo and Juliet where his own thoughts on the play- “Don’t drink it, I want to scream, she’s not really dead!”- contend with those of a snotty audience member: “Juliet is too small, she says frowning, and Romeo’s too thin”. From here he wonders if watching an Eagles game would be more satisfying. However, he eventually finds himself back in his seat and crying by the end of the third act. In “Twist Again,” Wilson recalls a romantic relationship from his teens in which a girl taught him how to properly perform both The Twist and a French kiss. With “After Seeing David Parson’s ‘Mood Swing,’” Wilson explains to the reader how this particular movie changed him: “At some point in the movie a little dam broke inside me…”. These poems as well as the others I have not mentioned excel in showing the reader how these moments have a positive effect on Wilson’s outlook.

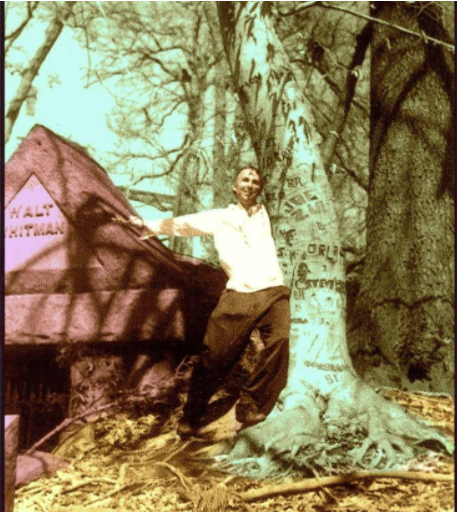

The book ends with the poem “Pas De Deux,” which imagines the poets Walt Whitman and Robert Frost becoming close friends as they climb a tree, ride the ferry, attend a baseball game, and “…sing the songs of the open roads not taken”. It’s moments like this and so many others that add up to make Dance with Me such a joy to read. It’s heartfelt and funny. I know its probably a rare thing to describe a book of poetry, but I found that reading this book was fun. It brings me back to that night in Fergie’s and makes me appreciate the art of performance and the camaraderie of people. I began that night hiding on the side of the dance floor, but when Rocky Wilson used his beautiful poetry to hold out his hand and ask me to dance, I took it. I am so glad I did. However, if you ever get a chance to cut in, please take it. I promise I will not be offended.

Philip Dykhouse lives in Philadelphia. His chapbook, Bury Me Here, was published and released by Toho Publishing in early 2020. His work has appeared in Toho Journal, Moonstone Press, everseradio.com, and Spiral Poetry. He was the featured reader for the Dead Bards of Philadelphia at the 2018 Philadelphia Poetry Festival.