FOUND IN TRANSLATION

I’m excited to get to write for Mad Poets about poetry in translation. If you’ve attended a lot of the First Wednesday readings at the Community Arts Center in Wallingford, you’ll have noticed that translators of poetry (often also poets themselves) present their work from time to time. It’s a task that fascinates me: the verbal texture of a poem is so important, but every language has its own, even languages as close as French and Spanish, or German and Dutch. Every language has things it does better than any other, and you can bet those things wind up in poems. How then can a translator bring the poem into a new language, keeping it a poem instead of a prose retelling?

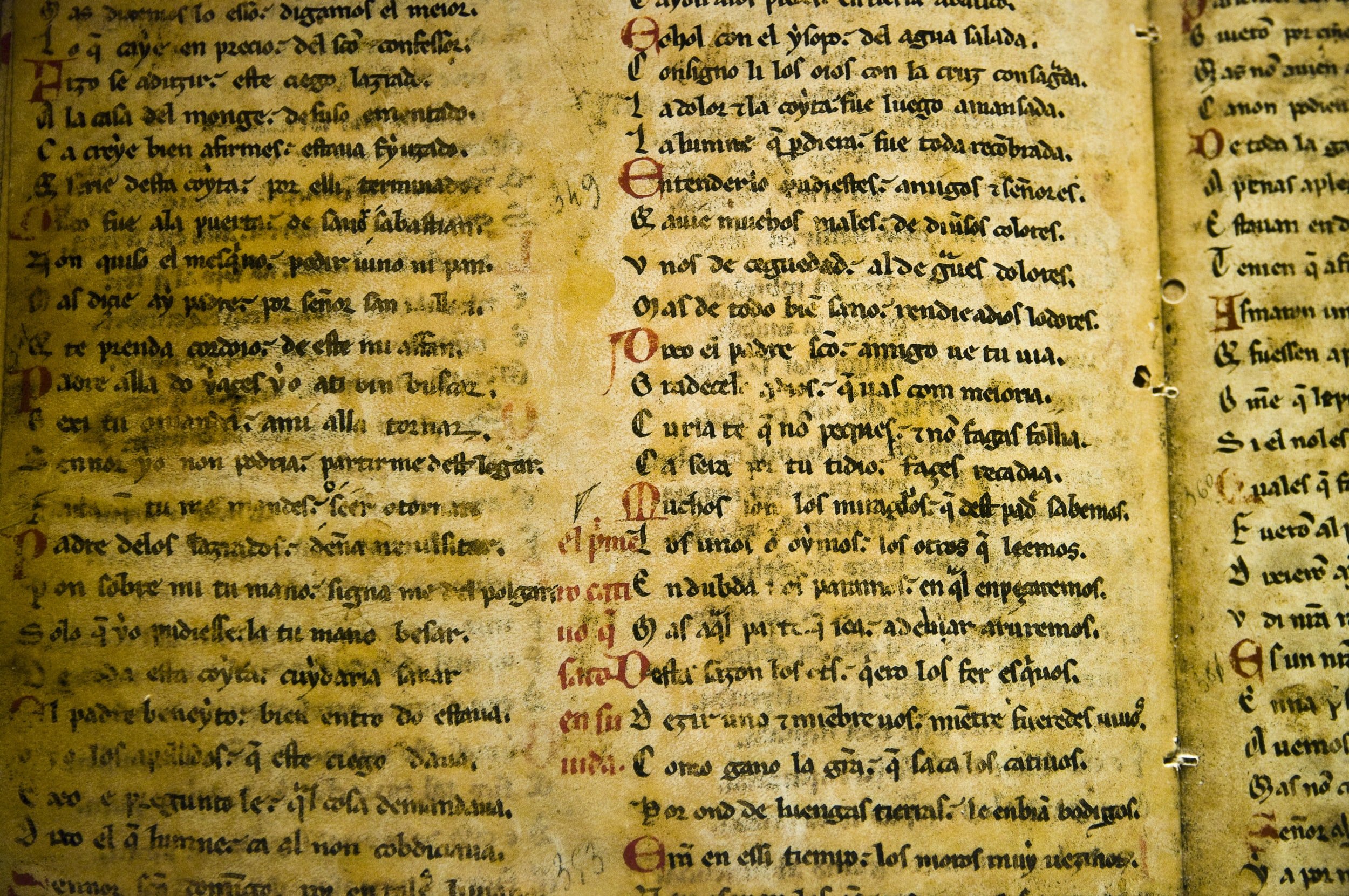

And yet poetry has exerted huge influence through translation, from Classical Greek or Latin shaping the writing of the Renaissance—or Italian sonnets spurring Elizabethan writing—to the very spare form of haiku flowering in other languages, including American English. Look closely at any big literary movement, and you’ll find translation at its roots.

Jerzy Ficowski, Everything I Don’t Know: Selected Poems, translated from the Polish by Jennifer Grotz and Piotr Sommer (Storrs, CT: World Poetry Books, 2021).

I hadn’t ever heard of Jerzy Ficowski (1924-2006)until this fall—unlike a lot of other important Polish poets of the 20th century, until recently he hadn’t been much translated into English. His translators, credited above, did a tour of readings, I got a copy of this book, and even though I don’t want to harp on Eastern European poets as I’m reviewing poetry in translation I need to bring it to your attention. I might also note that one of the blurbs on the back of the handsome paperback volume (the front has a striking picture of Ficowski, hand covering half his serious, aged face) is written by Ilya Kaminsky—a Deaf American poet originally from Odesa.

The translators felt that Ficowski has remained relatively unknown in the Anglophone world because that great tastemaker of Polish literature, Czesław Miłosz, did not include him in the canon he suggested to Anglophone readers. Ficowski’s creative and personal biography is certainly catchy: he took part in the Warsaw Uprising; after WWII and some university study he wandered with Polish Roma and wrote a study of their lives and culture, compiled an anthology of Polish Jewish folk poetry, translated poetry from multiple languages, and collected materials by and about Bruno Schulz, on whom he published a biography in 1967. You would expect a life of such event to produce poetry on important themes, and it does, but some of the best work in this volume is quite individual and not bound to time and place. The volume does not include any poetry in the original Polish, so as you read there is no need to skip things to see the translation. On the other hand, if you do know Polish you’ll have to find Ficowski’s work elsewhere to compare it to the translations.

Here is the beginning of one:

O Drawer!

Shelter for the sinful world,

o drawer, odyssey so vast,

made of oak, Homeric!

You will be the coffin

that once served as a cradle,

sinister imagination’s respite,

a hollow for words

written in whisper […]. (p. 15)

The poem’s deeper meaning becomes clearer if we imagine Ficowski, unable to publish his poetry for many years in Communist Poland, writing poems that went into the desk drawer since they had no chance of appearing in print. The phrase “written in whisper” suggests that “whisper” is its own language, not the pitch of sound that “a whisper” would mean. Since Polish does not distinguish between “a” and “the,” this is clearly added value from the translators.

Another example, this one in the cycle “from the Mythological Encyclopedia,” and numbered “i”:

Burners

The aureoles of stovetops.

The kitchen’s rings of hell.

The trained hoops of fire.

Red-hot bagels

eaten by rust.

Horseshoes of galloping pots.

The poker’s lovers

grinding in the fire of damnation.

And we cook our roast on their fervor. (p. 27)

Every single line here, funny and yet also dark with hints of hellfire, describes the burners on my stove!—Or this poem, its original published in 1968: like many of Ficowski’s poems, it refers back to the Holocaust and all of the Second World War, both especially bitter in Poland, as well as the general tragedy that the past cannot be changed or redeemed:

Today a Long Time Ago

I’m opening the door now

thirty years ago

Today I found the key

I meet you by the window

thirty years ago

You haven’t been waiting long

You’re just now young

I must prevent

everything that’s happened

Only the future

can’t be undone (p. 51)

But then a moment of vivid impersonal observation in the first two stanzas of “The Bird Beyond the Bird”:

Look

the bird is escaping from itself

by flapping

it’s bursting out of the nest of being

it wants to take a break from feathers

to slip out of being a bird

But it’s unable

to outpace itself

by even a bird’s beak (p. 68)

Another, later poem also and more explicitly refers to the losses of the Holocaust and the desire of survivors to remember and treasure the lost:

A Gathering of Stones

For Bronisław Anlen

The stones are gathering

And who was to come here

When there is stone upon stone

it means they’re acquainted

Here a stone says

kaddish

with its weight

its multitude

and stones the place

in the painless grass

The stones are gathering

Here sometimes an old man

will lug inside him

feldspar quartz and burden

and a wisp of green

bloodied with a rose

he will place it exactly

anywhere knowing

that he’s put it right into the hands

of his daughter Rachel

because everywhere are the hands

of his daughter Rachel

And even if it’s Miriam who gets the flower

so be it she also deserves

a petal of memory

even by mistake

The old man goes away

A stone stands up (pp. 82-83)

And last but not least in my selection, I have to share this one that reminds me of some of our Mad Poet Amy Laub’s water poems:

Incantation

o water that takes your own

shape

when you are very small

o single-celled

your name is a drop

you persist from high to low

not knowing a vessel

o closed-within-yourself

you perish when you open

and you’ll give birth to the sea

and be greeted

by salt and dolphin and columbus

and by susanna wallowing

her hair in rainwater

o droplet with nothing

to differ you from droplet

hollower of stone (p. 107)

Jennifer Grotz teaches at the University of Rochester and also directs the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conferences, which include sessions for translators as well as all the other good stuff. She was still something of a beginner in studying Polish when Warsaw poet, essayist and translator Piotr Sommer showed up as a visiting colleague, and they began working together on translations of Ficowski. Learning the subtleties of a language by working through translations (always “the closest reading”) sounds wonderful, and the results in this volume are generally excellent. Collaborative translation at its best sharpens the results, removing errors of understanding and drawing on twice the verbal inspiration. This book is highly recommended; I imagine that reading it would serve to inspire a poet as well.

Poet and translator Sibelan Forrester has been hosting the Mad Poets Society's First Wednesday reading series since 2016. She has published translations of fiction, poetry and scholarly prose from Croatian, Russian and Serbian, and has co-translated poetry from Ukrainian; books include a selection of fairy tales about Baba Yaga and a bilingual edition of poetry by Serbian poet Marija Knezevic. She is fascinated by the way translation follows the inspirational paths of the original work. Her own book of poems, Second Hand Fates, was published by Parnilis Media. In her day job, she teaches at Swarthmore College.